This is the last in a series on my adventures obtaining family records for dual citizenship. You can read early posts here, here, here, and here.

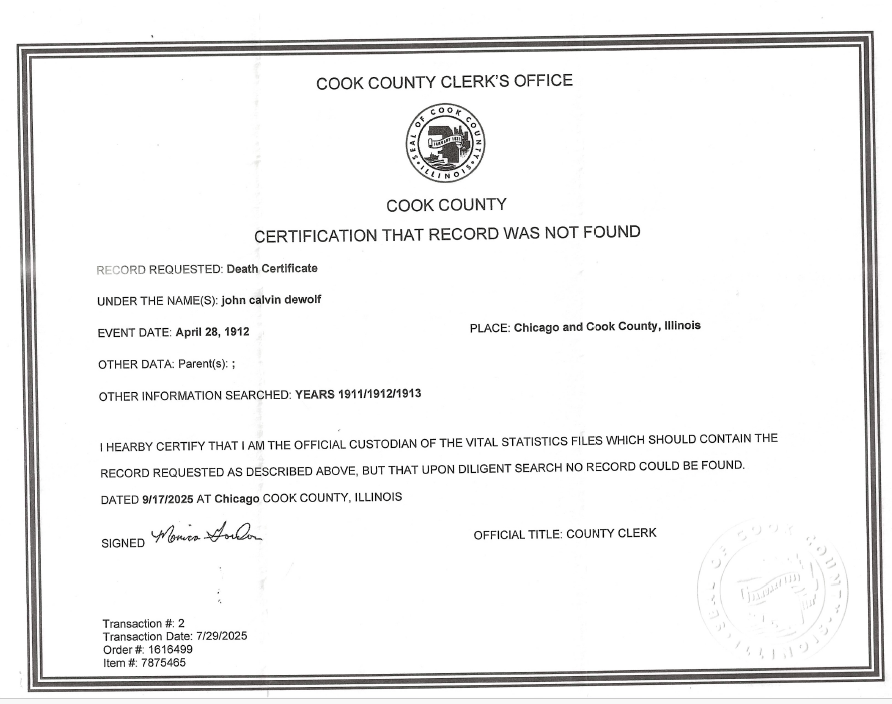

We had tried to get family documents from Illinois and Indiana in person and used email to obtain records from Florida and Arizona. Unbelievably, the online records had already been mailed to me while I tried to obtain the in person ones. Why? Because some states are more efficient then others. Illinois & Indiana, not so much.

We decided to drive two hours south east to acquire my father's birth record in Mercer County, Ohio. The clerk was warm and welcoming which was such a change from our experiences elsewhere. A problem surfaced quickly; the record for my dad in their computer claimed he had been born in 1939. Umm, no, he would have been the youngest enlistee in World War II if that was the case. I had a copy of the birth and death certificate which I shared with the clerk. She couldn't print a certified copy because whoever had input the information into the computer had made a typo. She went to search for a hard copy and found it. It was dated 1939. I believe what happened is that my father went to the office to obtain a certified copy so he could get his Social Security card. The clerk handwrote a new one and when my father looked at it he likely informed the clerk she had added the wrong year for his birth. I suspect she gave him a corrected replacement but kept the error record in the files. So, whoever input the info wasn't at fault.

It took over an hour and three transferred phone calls to Columbus for someone with tech knowledge to inform the clerk how to issue the birth certificate with the correct date. Meanwhile, others were arriving for records and I was surprised to learn that another person was also seeking dual citizenship.

With record finally in hand we decided to make an attempt to drop off the death records request that Gary refused to accept earlier in the week. So, it was back home again in Indiana. Sigh.

There’s no walk-in service at the Indiana State Department of Health in Indianapolis, and I knew that. What the website didn’t say was that you also can’t drop anything off. Still, I figured it was worth a try.

Two and a half hours later, we pulled into the very last spot on the sixth floor of a parking garage. $35 an hour. But hey, it was next to the elevator. Life was looking good.

Until it wasn’t.

Disappearing Buildings and Imaginary Signs

We couldn’t find the building. The address led us to a large office labeled Bank of America but surprise! It was actually the Department of Health.

Only in Indiana could a government agency masquerade as a bank to “save taxpayers money.” And if I were to complain to a legislator? I can already hear the syrupy voice:

“Now ma’am, we did you a big, beautiful favor by saving that signage cost, see?” (They always say “see.”)

There were no address numbers on the building. We finally wandered into another bank across the street, where someone kindly told us where to go.

If I had known what was coming next, I would’ve turned around.

The Plexiglass Purge

Inside the “Bank of Not-America,” a lone woman sat behind a desk topped with plexiglass, an absurd formality, given that it was the only furniture in the entire room besides a circular couch off in the corner.

She did not smile.

“We can’t take that,” she said flatly after I told her I had completed requests for death certificates.

I asked why.

“We don’t offer customer service.”

Well, clearly, that must be the vital records motto throughout Indiana.

I explained I’d driven from the northeast corner of the state because Gary refused to issue the records and whenever I mailed requests, they disappeared into the void.

“We’re very backlogged.”

At that point, my husband, officially done, asked if he could sit down. She pointed silently to the one chair in what was once the vestibule.

I asked where the nearest post office was. My thought: if I mailed it from just a few blocks away, maybe they’d actually receive it. Silly me.

She offered to draw me a map. I handed her my notebook.

That’s when it got weird.

Enter: The Scowler

Out of nowhere, a man’s voice boomed behind me:

“What can I help you with?”

Startled, I turned to see a tall man with a very unfriendly expression and a gun. Yep, it was an officer of the law. I had no idea he was even in the room.

I answered, “There’s nothing you can help me with.”

Apparently, that was the wrong thing to say.

He started yelling, “Tone it down! Tone it down!”

I wasn’t raising my voice. I hadn't even been speaking when began yelling. But suddenly I could see it all: me, tackled to the ground, handcuffed, arrested for attempting to find a post office to send for three death records that the department who issues them refused to take.

The woman at the desk piped up, “She’s a nice lady, she’s not a problem.”

He replied, “I’ll handle this.”

Handle what? Was he going to walk my envelopes to the post office for me? Hand-deliver them to the Department of Health? Please, don’t tease me.

He eventually got bored and retreated to the sofa, where another officer sat watching the show with amusement.

Yep, fun and games intimidating an old lady genealogist. Karma, baby. Let it be soon.

The Map of Madness

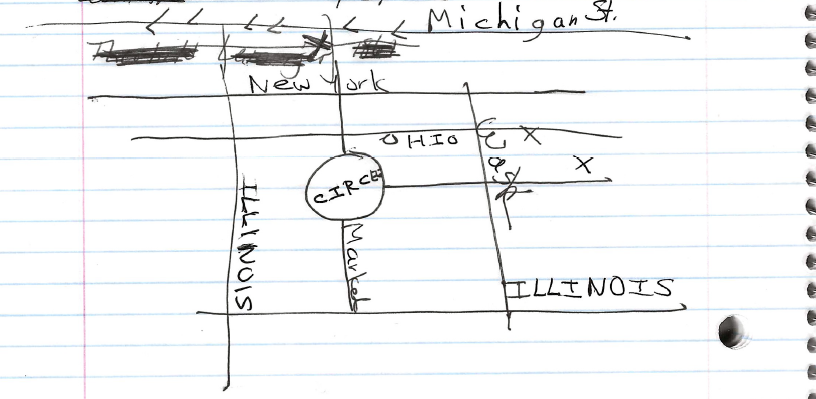

The woman finished her map and handed it to me proudly, saying, “I’m not much of an artist, but I think I did a good job.”

I looked at it: three horizontal lines, three vertical lines, a circle, and three X’s because she “wasn’t sure where the post office was.” Also, she misspelled Washington. It had taken her five full minutes to draw this.

I stared at the page, silently. She looked sad that I didn't appreciate her work.

I asked if it was walkable, thinking I could leave the car parked. “If you’re good at walking,” she said.

Not knowing what that meant, I asked how far it was.

“Maybe five or more blocks.”

Sure. We’d drive.

She said she should probably give me the address as well, there was another post office nearby, but she wouldn’t send me there because “it wasn’t very good.”

(Pretty sure that’s the one where all my mail has vanished into the ether.)

She had to call someone else to find the name and address of the post office she'd just drawn a map for.

I left, sad for the state of public service and even sadder that this was the outcome of my tax dollars.

The Last Gasp

It was now pouring rain.

I parked in what was probably an employee lot behind the post office and left my husband in the car in case it needed to be moved.

Inside: long line. No one at the desk. Classic.

Thirty minutes later, I sent off two envelope, each with certified requests for death certificates, destined for a building two blocks away.

Only in America can it take three days to deliver a letter that far.

It was scheduled to arrive on Saturday when no one is there to sign for it. Of course.

So maybe Monday. Maybe never.

And when it inevitably goes missing? I planned to take my receipt to my local post office, and they’ll tell me I have to go back to Indianapolis to get a refund.

At this point, I’m starting to think dual citizenship was absolutely the right decision. Even with all the hassles. Even with the yelling. Even with that map.

Next week, to begin a new year, I'll post a a look back at the favorite blog posts selected by readers for 2025. Stay Tuned.