In November–December 2026, I wrote a series of blog posts about my experience obtaining records for dual citizenship. Since then, I’ve received weekly messages from people interested in pursuing dual citizenship themselves.

Let me be clear: I didn’t write those posts to discourage anyone. I wrote them to be transparent.

If I were hiring someone to help me with a complex, expensive, emotionally charged process, I would want honesty about the cost, the delays, the bureaucracy, and the unexpected hurdles. That’s what I aim to provide my clients in every aspect of my work.

One important disclosure: I contract with citizenship.eu and do not take private clients for dual citizenship applications. My role here is to share my experience, not to sell services.

By early December, I had finally received every record I requested, starting back in July. The last document to arrive was from NARA–DC: my grandmother’s ship manifest, which came on December 3. I didn’t blog about that particular request because it was made online but it came with its own challenges. The NARA website doesn’t always cooperate, the government shutdown delayed retrieval, and I couldn’t find a genealogist available to physically retrieve the record in Washington, D.C.

So yes, even the “easy” requests weren’t always easy. I then had to send it off to be apostilled. The record was returned to me 3 days ago.

If you’re considering dual citizenship, here’s what I wish someone had told me before I started.

- Contact the consulate before you do anything else. Not after. Not halfway through. Before. This ensures you understand exactly what they require and it puts you on their radar. In my case, I was emailed detailed instructions which were clear and helpful.

Begin acquiring records and brace yourself. This phase is both expensive and time-consuming. I ordered two certified copies of every record and obtained several documents I didn’t initially plan to submit, simply to have a complete, redundant set in case anything was lost or damaged.

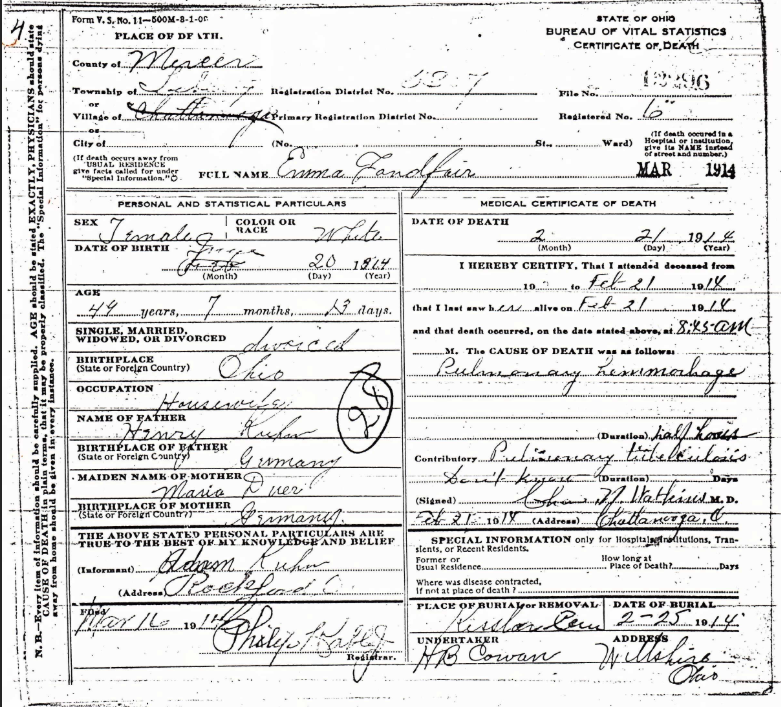

My total cost for records was $1317.80. That included my immigrant grandmother’s birth, marriage, death, ship manifest, and naturalization records; my mother’s birth and baptismal records (because no civil birth record existed), marriage, and death certificates; my own birth and marriage records (both church and civil, because my given name differed); my husband’s birth certificate; and the birth certificates of my adult children and their partners. Some of us all also needed to update our passports which were due for renewal.

I also obtained records I didn’t expect to submit, death certificates for my great-grandparents, my grandfather, and my father, along with his birth certificate, just in case questions arose about lineage. I may not need them, but I sleep better knowing they exist. Those costs are not included in the above total.

- Every document must be apostilled. This is a separate authentication process that verifies the legitimacy of public documents for international use. Apostilles add both time and cost, and the process varies depending on whether the document is state or federally issued.

All of the records I plan to submit require apostilles, including birth, marriage, death, naturalization, ship manifests, and FBI clearance. Each record must be sent to the appropriate authority; the state records to the Secretary of State, federal records to the U.S. Department of State, along with forms and fees.

So far, my apostille costs total $305.00, with one state still remaining. I plan to handle Illinois in person because mail processing there is painfully slow. My mailing costs alone reached $92.45 and that amount increased when Florida rejected my apostille request because I included a church marriage record they would not certify. That error added a month-long delay and another trip to the post office.

Here’s my strongest advice: always include a prepaid return envelope with tracking. It costs more, but if documents are sent back by regular mail, they can disappear forever.

- FBI clearance was surprisingly the easiest step. You complete the application online and should not include your Social Security number, since the document will be sent overseas. After submitting the form, you’re directed to a local post office for fingerprinting. We opted for electronic fingerprints and received results almost immediately, before we even paid the fee while waiting in line at the site.

If electronic fingerprinting fails, you’ll need to use a paper card and mail it in, which adds time and cost. Ironically, the FBI clearance often considered the slowest part, was the fastest, aside from the three months it took for the apostille.

- You will need a certified translator. Ask the consulate if they have preferred translators, or research carefully through reliable sources (yes, Reddit threads can be useful here). Certified translators are approved by the courts of the country where you’re applying, and they are expensive.

I haven’t completed all translations yet, but the estimated cost will be around $5,000. Some translators will assist with applications, biographies, and statements of intent; others will not. I chose to work with a genealogist who obtained my grandmother’s baptismal record, a trusted colleague who kindly offered a discounted rate.

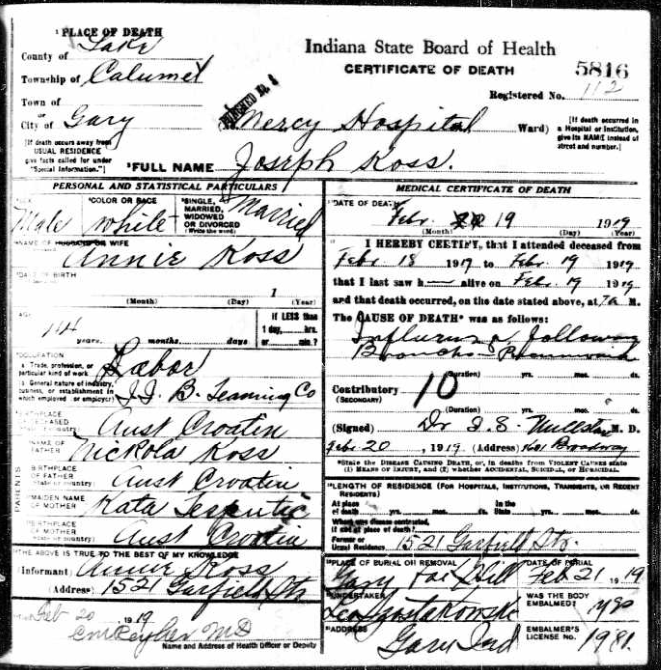

- This is where patience goes to die, acquiring records from the country of origin is not easier than obtaining them in the U.S.

In my case, it took two months to obtain a single certified record. The office closed for two weeks for vacation. When the genealogist arrived at the scheduled appointment, she was told, incorrectly, that the church had to issue the record. A week later, the church sent her back to the civil office. Then the church had to write a letter instructing the civil office to release the document. Two more weeks passed before the record was issued. Then it took three weeks for international mail to deliver it.

No one was rude. No one was helpful. Bureaucracy is bureaucracy everywhere.

- Understand that dual citizenship is a process of hurry up and wait. Once our records are translated, my family will wait until late October for our consulate appointment in Chicago. There, a consular employee will review our documents to ensure we are submitting the correct ones. Copies will be retained by the consulate, the certified apostilled originals with transcription and that apostilled sent overseas (and yes, I ordered extras because I’m paranoid). There is a fee for submission that is reasonable, considering how much was already spent.

After submission, the waiting begins, sometimes two to five years or more.

I also incurred costs for hotel/gas/parking/meals while we tried to obtain records in person. ($703.47).

So far, I've spent less than average as typically dual citizenship can cost between $10,000-20,000.00. My cost was less because I sought out the records on my own in all but one case. I also did not hire a lawyer which is sometimes needed, depending on the country and the situation.

So why would anyone willingly endure this?

Everyone’s reasons are different. For my family, it’s about global mobility and connection. We still practice the customs of my grandmother’s culture, and when we are in Croatia, it feels like home. There should be a language barrier because our Croatian stinks but somehow we razumjeti (understand). I'll be working on improving while we wait for the decision.

Others pursue dual citizenship for healthcare, education, lower living costs, or expanded career opportunities. Business owners may relocate to continue serving existing clients while building new markets. And many younger applicants, especially those in their twenties, simply want options. I hear that sentiment often.

Dual citizenship is not a weekend project, a budget-friendly endeavor, or a fast-track solution to anything. It is expensive, slow, frustrating, and emotionally taxing. It requires organization, patience, and a tolerance for bureaucracy that most people don’t realize they lack until they’re knee-deep in certified copies and apostille forms.

But for those who value connection, opportunity, and the ability to move through the world with greater freedom, it can be worth every delay and every dollar.

My goal in sharing this update isn’t to persuade you one way or the other. It’s to help you make an informed decision. If you choose to pursue dual citizenship, go in with open eyes, realistic expectations, and a very good filing system. And if you decide it’s not for you, that’s not failure, that’s wisdom.

If this process has taught me anything, it’s that knowing what you’re walking into makes all the difference.