Today’s lesson is about a bad habit I picked up early on: not saving my source information.

I somehow convinced myself that if I ever needed to revisit a record, I could just find it again.

Umm… no. Just, NO.

I gave a hint about when this habit started back in Lesson 1. Let’s rewind to the “olden days” of genealogy—pre-2017. Back then, FamilySearch.org offered a microfilm lending program. You could request films from their Salt Lake City library, and they’d mail them to your nearest affiliate FamilySearch Center. Not everything was digitized. Actually, very little was.

When I began taking genealogy seriously—beyond hobby level—this was the norm. You went to your local center, filled out a request, waited for the film to arrive (by actual snail mail), then returned during limited hours to view it. If someone else was hogging the one microfilm reader attached to the printer, too bad. You either came back later or stared at the record and hoped you’d remember what it said.

There were no smartphones early on. No screenshots. Sometimes you could print, but not always. So I often didn’t save the record at all.

One example still haunts me.

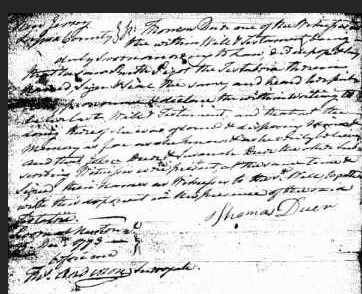

Back in the early 2000s, I found a will dated 1793. Two of my ancestors—my fourth and fifth great-grandfathers, John and Thomas Duer—had signed it as witnesses for a neighbor. No relationships were noted, of course (because why would records make things easy?). But it was the only document placing both men in the same New Jersey township at the same time.

Years later, when I submitted my DAR application through this line, I used DNA to bolster the case. I wanted to revisit that old will—see if my now-trained eyes could spot something I missed. But I had never saved it. And it still wasn’t viewable from home.

So I made the trek—45 minutes each way—to the nearest affiliate library. I found the film, loaded it, and saved the image to a thumb drive.

Or so I thought.

Back home, I plugged in the drive. Nothing. Nada. Empty.

Cue the stages of genealogical grief: disbelief, denial, rage, regret.

I drove all the way back and did it all over again. This time, I emailed the document to myself, saved it in two places, and mentally kicked myself for not doing it right the first time.

Since then, I’ve changed my approach completely: if I find a record, I save it. Period. Hard drive, cloud storage, email backup—whatever it takes.

And you know what? It’s not paranoia. It’s preparation.

With so many records being pulled offline or locked behind new restrictions, saving your sources isn’t just smart—it’s essential. I’m even considering publishing a companion volume to my family history books, filled with clips of the actual documents I’ve cited: baptisms, marriages, deaths, censuses, probates, land deeds, gravestones, voting rolls, tax lists—you name it.

Because proof matters.

Sure, I’ve included citations in my books. But is that enough anymore? Many of the records I reference are no longer accessible. And barring a legislative miracle, they won’t be available again in my lifetime.

Today, that will is available on Fold3 but who knows if it will remain there. So here’s the takeaway: don’t assume you can find it later. Save it. Label it. Back it up.

Because someday, you’ll need it again—and you’ll be glad you did.

Terrific advice: Save the record, label it correctly, be sure you can find it again (and know where you found it originally).

ReplyDeleteOh, we all did that when we first started, though I kept written notes because I was too cheap to make photocopies. You're right, some items are no longer available to us. Save it when you can.

ReplyDeleteSo many of us have learned this lesson the hard way...About a decade ago I found a mention of my paternal grandmother and her father. I didn't screencap it or save the link - it mentioned something key. Even though, as a historian, I should have known better, I assumed it would always be there. Yep, it's gone. Still kick myself every time I think about it.

ReplyDeleteSimilarly, I learned about online genealogy sites losing access to key record image set - also the hard way. Now I know better and screencap or download EVERYTHING! It's why I need a 2TB hard drive and 2 external backup drives!